Little Cottonwood Canyon is now a Historic Climbing Area

On August 5th, 2024, Little Cottonwood Canyon (LCC) became America’s first recreational climbing area to be listed in the National Register of Historical Places.

This advocacy work celebrates the legacy of climbing in LCC that lives on today. Recognizing LCC climbing and its surrounding landscape for its historical value elevates the need to protect and preserve this special place in the hearts and minds of Utahns.

As climbing continues to evolve, the routes and the passion for where we climb remain the same. We have a challenge and responsibility to preserve and protect these iconic climbing landscapes, rich with historical value.

Because we can save a place a thousand times, but lose it only once.

-

A gathering centered around the designation will occur September 25th, 2024 from 5:30-6:30PM in the Lower Little Cottonwood Park & Ride.

Speakers & option for a one-mile hike along the historical Alpenbock Loop led by SLCA staff.

-

The Little Cottonwood Canyon Climbing Area’s period of significance is 1962-1974. Both technical and non-technical climbing in Utah pre-dates this period; however, those activities are less documented. The Alpenbock Climbing Club established routes in the historical area and beyond. They served as the county’s first mountain search and rescue unit.

This period of significance spans from when Alpenbock Climbing Club members Ted Wilson and Larry Love established the first recorded climbing route to the time when route and technical climbing knowledge was passed person-to-person, rather than guidebooks or apps. It also captures the rise of the Leave No Trace movement in climbing - embraced and promoted by the Alpenbock Climbing Club—and the winter/ice climbing led by George Lowe.

The Little Cottonwood Canyon Climbing Area holds statewide significance as an excellent representation of a culturally important district in the areas of Recreation and Social History in Salt Lake County, Utah.

In the area of Recreation, the district is significant for its contributions to the development of early rock climbing, the establishment of “classic” climbing routes, the pioneering of hard-rock climbing technology, and the fostering of local enthusiasm for climbing as an outdoor activity. The distinctive granite formations within the historic district have remained unchanged since 1962 and are closely interconnected within a relatively small geographic area.

In the area of Social History, the district is significant for its association with the local Alpenbock Climbing Club and with individuals whose activities were critical in building the Utah climbing community and connecting it with the national climbing community through recognized figures such as Yvon Chouinard, Royal Robbins, Fred Beckey, and Layton Kor. These national figures helped legitimize climbing in Little Cottonwood Canyon, elevated the status of the Alpenbock Climbing Club, and contributed to the spread of international climbing culture. Notable local climbers were highly proficient and internationally experienced, working in search and rescue locally and in the Grand Tetons throughout the 1960s.

Read the full proposal here.

---

From 2022-2024, the SLCA worked to nominate lower Little Cottonwood Canyon’s (LCC) as a historical climbing area. This advocacy work celebrates the legacy of climbing in LCC that lives on today. Recognizing LCC climbing and its surrounding landscape for its historical value elevates the need to protect and preserve this special place in the hearts and minds of Utahns.

With the support of grants, we were able to hire specialist Kirk Huffaker Preservation Strategies to write the historical nomination. On August 5th, 2024, lower Little Cottonwood Canyon become America’s first recreational climbing area to be listed in the National Register of Historical Places. This could not have been accomplished without the expertise of volunteer SLCA Policy Committee Member and Assistant Director of the American West Center, John Flynn. A huge thanks to University of Utah Librarian Tallie Casucci and her library colleagues for their dedicated work on this project. We appreciate the endorsement from the Forest Service and the Utah State Historic Preservation Office.

What

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic value." The NRHP is a program of the National Park Service and is locally administered by the Utah State Historic Preservation Office.

The Little Cottonwood Canyon Climbing Area Historic District holds statewide significance as an excellent representation of a culturally important district in the areas of Recreation and Social History in Salt Lake County, Utah. Its significance is recognized on a statewide level due to the rapid development of climbing as a recreational sport within the district, which was primarily driven by one group—the Alpenbock Climbing Club.

Where

The Little Cottonwood Canyon Climbing Area is located at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon, south east of Salt Lake City, UT. This area can be accessed from two main areas: the Little Cottonwood Park and Ride via the Alpenbock Loop trail or Pipeline trail and the Grit Mill Parking area via the Grit Mill Trail.

Climbing information such as routes and bouldering can be found on Mountain Project and in the guidebookA Granite Guide - Ferguson to Lone Peak.

-

The Alpenbock Trail is named in honor of the Alpenbock Club. The club's members were the first ascentionists of many of the classic climbing routes in Little Cottonwood Canyon. Although people had tried to climb the granite as early as 1930, the first documented climbing route in Little Cottonwood Canyon was done by Alpenbock Members: Ted Wilson and Bob Stout. Established in 1961, Chickenhead Holiday opened the eyes of Alpenbock Club members and started an era of technical climbing in Little Cottonwood Canyon.

The Grit Mill Connector Trail was named after a mid-20th century poultry grit production facility that was removed in 2014 as part of the remediation of the site. The granite grit produced at this mill was supplied to turkey farms in the area where it was fed to the birds to help with digestion.

-

The Salt Lake Climbers Alliance is making a short film! But we need your help and support to bring this story to the big screen!

Delve into the history of legendary Wasatch climbers in a short documentary, celebrating our climbing legacy in Big and Little Cottonwood Canyons, and the enduring spirit of the Alpenbock Club amid contemporary preservation challenges.

Learn more here.

PRESS

Interactive Historical Hike

Tour Description

While short in length (1.5 miles), the hike is moderate in difficulty due to the terrain. It is not recommended for those with leg injuries, balance issues, or young children. By attending a tour, you assume all risk associated with participating in a physical activity of this nature.

Pre-Tour Reminders

Before you begin the tour, please take this opportunity to use the restroom and ensure all valuables are secured in your vehicle, as theft can be an issue in these canyons. Be prepared to hike for approximately 1.5 hours, and bring any sun protection, clothing layers, and water you may need.

This landscape is home to rattlesnakes and ticks, so please watch your step and wear closed-toe shoes. We also recommend long pants, as you may encounter poison ivy. Be sure to check for ticks after the tour.

Stop 1 – Welcome & Introduction

*See map above

Welcome to the historic Little Cottonwood Canyon Climbing Area, the first recreational climbing site in the United States to be listed in the National Register of Historic Places. This tour, presented by the Salt Lake Climbers Alliance, will highlight the natural, scenic, cultural, and historic character of this remarkable site, as well as the unique individuals who pioneered climbing routes here starting in the late 1950s.

Geological & Geographical Context:

Little Cottonwood Canyon is a glacially carved U-shaped valley. The base elevation is 5,374 feet, rising to 8,720 feet at the end of SR-210 above Alta Ski Resort. Albion Basin once held a glacier that deposited massive boulders and carved canyon walls as it receded. Surrounding the valley are 11,000-foot-high granite peaks, providing abundant terrain for backcountry skiing, hiking, camping, and climbing.

Land Acknowledgment:

Long before climbing, this land was traversed and stewarded by the Indigenous peoples of Utah — including the Paiute, Ute, Goshute, Shoshone, and Navajo Tribes. Little Cottonwood Canyon served as a vital thoroughfare that benefited all of these Tribes prior to colonization. We honor and respect the resilience and stewardship these native communities have shown across the state of Utah.

Climbing Legacy:

This area is world-renowned for the quality of its climbing. As Yvon Chouinard, founder of Chouinard Equipment (now Black Diamond) and Patagonia once said:

“We choose to believe that the granite is alive. If life is movement, then rock… is alive. It’s a harmless concept that adds a lot of enjoyment and respect and responsibility to our lives.”

The canyon features rock types ranging from granite to quartzite to limestone, but it is the white granite—quartz monzonite—that defines Little Cottonwood Canyon climbing. With less quartz than true granite, quartz monzonite fractures granually, similar to the granite of Yosemite.

Two geologic features make this rock special for climbers:

Chickenheads: Protrusions of harder rock, resistant to erosion, named by Ted Wilson and Bob Stout in their route “Chickenhead Holiday.”

Cooling joints: Vertical crack systems formed as the rock cooled, ideal for climbing protection and technique.

These formations result in textured, geometric surfaces that provide excellent friction for climbers.

Site Overview:

The historic climbing site is located on the north slope of lower Little Cottonwood Canyon and includes:

6 climbing areas

9 bouldering locations

2 trail segments

The site is traditionally divided into:

Upper half: Vertical climbing (requiring ropes and gear)

Lower half: Bouldering (no ropes)

Stop 2 – Alpenbock Trail + Alpenbock Club

*Show Photo 1 – The Club in 1961

This trail is rightly named after the climbing club that pioneered climbing here in the canyon. The Alpenbock Club was a group of adventurous high school students who sought new challenges. They chose the name “Alpenbock,” which they believed meant “mountain goat,” though the strict German translation is “alpine sawyer.” The term also references the Alpine longhorn beetle. Without the internet, the translation was a bit questionable—but the name stuck.

The club was founded in the late 1950s by a small group of students at Olympus High School, inspired by films about climbing Everest. They were not only motivated by personal adventure but also committed to climbing safely, respectfully, and to documenting their activities.

Thanks to their skills and initiative, the Alpenbock Club became the first volunteer search and rescue crew in Salt Lake County, and laid the groundwork for what would eventually become today’s Salt Lake County Search & Rescue.

The period of significance for this site—during which the Alpenbock Club was most active—spans 1962 to 1974.

*Show Photo 2 – Club members rigging a litter during a training exercise

A quote by climber and author Ron Kauk feels especially appropriate at this stop:

“It’s really all about the ones who came before, who inspired us to prepare ourselves — to develop the physical strength and technique to enter the unknown with confidence and take care of ourselves in this environment.”

*Show Photo 3 – The original club patch

* Show photo on the back of photo 2 - Alpenbock Climbing Club Scrapbooks

The Alpenbock Climbing Club Scrapbooks (Volume I and Volume II) are now available online in the J. Willard Marriott Digital Library. The two scrapbooks document the activities of the Alpenbock Climbing Club from 1961 to 1964 and are first guidebooks to climbing around Salt Lake City. The scrapbooks contain black-and-white photographs taken by Club members during their climbs, handwritten descriptions (oftentimes including what they brought to eat on the climbs) as well as clippings from local Salt Lake City newspapers and climbing magazines, typed reflections from club members about climbs, written descriptions and drawings of climbing routes, communications and agendas related to club activities, and other ephemera, including a cloth Alpenbock Club patch. The scrapbooks contain routes and reports from other climbing areas, including the Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming and the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California.

We are currently on a segment of the Alpenbock Trail, a project led by the Salt Lake Climbers Alliance (SLCA)—a local nonprofit dedicated to rock climbing stewardship and advocacy.

Major support for this trail came from:

Utah Division of Outdoor Recreation

Recreational Trails Program

The trail plan was approved by the Forest Service in 2012, and the main route was constructed to Forest Service trail standards, with final completion in November 2020.

You’ll see examples of:

Forest Service standard trail work (along main trail)

Climbing route spurs with rock stairways and steeper terrain

The trail is now used year-round by hikers, trail runners, and climbers.

As of April 2021, the Alpenbock Loop Trail is the largest climbing access trail project ever completed on Forest Service land in the United States.

In 2023, the Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) approved an 8-mile gondola as its long-term solution to address traffic congestion in Little Cottonwood Canyon, following a five-year environmental review process. However, the gondola isn’t expected to be operational until 2043–2050, and many advocates (including the SLCA) argue it poses the most significant threat to climbing access in the Wasatch in history. Critics contend that such permanent infrastructure should only be considered after less damaging solutions—like expanded electric bus service, tolling, and traffic mitigation strategies—have been fully attempted. The gondola would irreversibly impact the canyon’s natural character, threaten the nationally recognized Lower LCC Climbing Area Historic District, and cater primarily to ski resort users while ignoring year-round, dispersed recreation needs. Additionally, it fails to solve the traffic problem, allows continued single-occupancy vehicle use, is projected to cost over $1 billion to tax payers, and represents an inequitable and environmentally unjust solution for the Wasatch Front. One of the angle stations for the gondola would be in the parking lot that we just left compromising limited dispersed use parking that accesses our public lands.

Stop 3 – Equipment

*Point out Bong Eater

The first ascent of this 75-foot pitch, known as Bong Eater, was completed in 1964 by Warren Marshall and Lenny Nelson. In 1974, George Lowe and Pete Gibbs became the first to free climb it. The climb is rated 5.10d on the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS).

About the Yosemite Decimal System

The YDS was developed in the 1950s and evolved from a hiking difficulty scale.

Class 5 terrain signifies technical rock climbing.

Routes start at 5.0 and increase in difficulty.

Beginning at 5.10, ratings include a–d suffixes (e.g., 5.10a, 5.10b) for more precision.

The system is open-ended—as of 2023, the hardest rated climb is 5.15d.

Vertical routes like this typically require:

Use of ropes and protection

Climbers ascending in pairs or teams, belaying one another

Descents via rappelling or hiking off

What’s a “Bong”?

A bong, sometimes called a bong bong, is the largest type of piton used to anchor into rock.

Made from sheet aluminum

Named for the distinctive sound it makes when hammered into place

Used to protect climbers from falls or assist in aid climbing

*Show Photo 5 – A Chouinard Company bong bong piton

A piton is a metal spike driven into a rock crack using a hammer.

Acts as a fixed anchor

Has a ring or eye hole for attaching a carabiner

The carabiner connects to the climbing rope for protection

This route likely required or lost many pitons in early ascents—hence the name Bong Eater.

There are still piton scars in the rock—visible remnants of earlier climbing eras.

While they are no longer used regularly, these scars are considered character-defining features of historic climbing.

Today, pitons have been largely replaced by:

Camming units

Nuts (passive protection)

These tools perform better and minimize damage to the rock, reflecting the shift to clean climbing practices.

Stop 4 – Climbing Technique

*Point out each route from left to right

The feature in front of you, known as Mexican Crack, has seven historic routes:

Three were first climbed in 1963

The most recent in 1970

Ranging in height from 80 to 300 feet

Difficulty ratings range from 5.7 to 5.11a

The wall is part of what’s known as Crescent Crack Buttress.

Route Naming

Traditionally, the first ascentionists name the routes.

There’s no formal process—names are often influenced by:

A climber’s life experiences

Running jokes

Creative whims

For example, this wall includes routes named:

Crack in the Woods

Hand Jive

No Jive Arete

Spanish Fly

Mexican Crack

3 Amigos

Grunting Gringos

If you’re curious, the Granite Guide and MountainProject.com are excellent resources to explore more stories and route histories.

Granite and Joint Patterns

Granite, the dominant rock type here, provides geometric joint patterns that:

Help climbers predict rock quality

Offer natural paths for placing gear

Create crack systems ideal for climbing

*Show Photo 6 – A club member using friction to ascend in attire of the era

This canyon is a world-class granite climbing area—but it demands a unique technique called technical slab climbing.

Climbing Technique: Friction & Chickenheads

Climbers often rely on friction, using shoes and body position to stick to the rock.

“Smearing” is when you place your foot flat against the rock, relying on rubber friction—like smearing cream cheese on a bagel.

With no defined footholds, it can feel like standing on nothing.

Luckily, climbers sometimes encounter “chickenheads” (also called knobs)—rounded, blob-like protrusions that can be used for hands or feet. These are common in weathered granite areas such as:

Little Cottonwood Canyon

Yosemite

Joshua Tree

South Platte, Colorado

Environmental Considerations

Friction improves in cooler temperatures, which is why many climbers visit year-round.

Even as you hike, you’re using this same friction. But beware of “kitty litter”—tiny, loose granite particles that reduce traction and increase difficulty on climbs and trails.

Regional Rock Variety in Utah

Utah offers a broad spectrum of climbing experiences:

Quartzite in the Uintas: steep, sharp, and edge-heavy

Cobble climbing in Maple Canyon: like climbing a cemented wall of river rocks

Sandstone cracks in Indian Creek: vertical splitters requiring jamming technique

Each rock type shapes the climber’s experience and the skills required.

Stop 5 – Viewshed

*Point out The Coffin (left) and The Sail Face (center)

*Show Photo 7 – The scrapbook illustration of the Wilson-Love route on the Sail Face and route on the Coffin

The Sail Face has three historic routes, each first climbed between 1962–1964.

Approximate height: 100 feet

Difficulty: 5.7–5.8

The Coffin, located on the right side of Crescent Crack Buttress, was first climbed in 1963 by Alpenbock Club members Court Richards and Jim Gully.

Difficulty: 5.9

*Show Photo 8 – Ted Wilson in 1962 on the first attempt of The Coffin

Importance of Viewsheds

This is a great opportunity to reflect on how viewsheds—what you see to and from a climbing area—are integral to the climbing experience.

In historic preservation, viewsheds are a component of the historic setting.

A sense of openness and naturalness remains strong in Little Cottonwood Canyon.

Despite modern development, the experience today is remarkably similar to that of early climbers.

Climbing is not just about reaching the top—it’s about the journey, the challenge, and the view that rewards your effort.

Little Cottonwood Canyon offers:

Towering granite walls

Expansive views both up and down canyon

Scenic lines into the Salt Lake Valley

These views allow modern climbers to connect with the dramatic natural setting and appreciate the legacy of those who climbed before.

Quote from Alpenbock climber Larry Love:

“We made it, and we’re still breathing. Just a great feeling of having a friend there with me and the view.”

Stop 6 – Circulation

*Point out the trail going down from pipeline

From the time of the Alpenbock Club through the late 2000s, climbers accessed the base of climbing sites via a web of wildlife and social trails. These informal routes:

Required bushwhacking through natural areas

Often changed from visit to visit

Contributed to erosion and degradation of the landscape

There was no standard approach—no two climbers took the exact same way twice.

The original main climbing access trail from SR-210 is located here.

It was convenient because it fell between two major bouldering areas.

It connected to the already established Pipeline Trail.

Back then, the goal wasn’t a nicely graded hike—it was simply getting to the climb.

Some climbers even joked that the steep, loose social trails were more difficult than the climbing routes themselves.

Leave No Trace and Clean Climbing Legacy

The Alpenbock Club was ahead of its time in promoting values that align with today’s Leave No Trace principles.

Their early commitment included:

Minimizing impact to the natural environment

Transitioning from damaging pitons to clean gear like cams and nuts

(passive protection that doesn’t scar the rock)

That ethic of care lives on today through the Salt Lake Climbers Alliance and its stewardship efforts.

Stop 7 – Bouldering

*Take the group around to a northeast-facing vantage point of Copperhead and Shothole

Welcome to the Secret Garden, one of the two historic bouldering areas in Little Cottonwood Canyon.

In the era of the Alpenbock Club, the term bouldering wasn’t widely used. However, they used these boulders for:

Training

Warming up

Skill development

—practices that laid the foundation for what would become a major discipline in climbing.

By the 1990s, bouldering had become popularized and named as its own style. Today, it’s a growing sport, with USA Climbing athletes and Olympians training on these very boulders to build their mental and physical strength.

Boulders here:

Copperhead Boulder (larger)

Shothole Boulder (to the right)

About Bouldering

Takes place on shorter rock features (typically no ropes)

Descents are usually by jumping down or walking off

Protection comes from crash pads (portable foam landing pads)

Often a solo or meditative activity, but also social and collaborative

Key benefits:

Minimal gear

High accessibility

Deep personal connection to specific problems and stone

These granite boulders provide:

Shady, protected climbing in summer months

High-quality stone with both faces and cracks

Dozens of documented boulder problems, with route ratings from V0 to V13

Cultural and Historical Context

Many of the boulders show blast marks—scars left from quarrying granite for construction of the Salt Lake Temple by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

*Show Photo 9 – LDS workers at the granite quarry in Little Cottonwood Canyon

These blast holes have even become part of the climbing problems, adding unique features and challenges.

Land Access and Stewardship

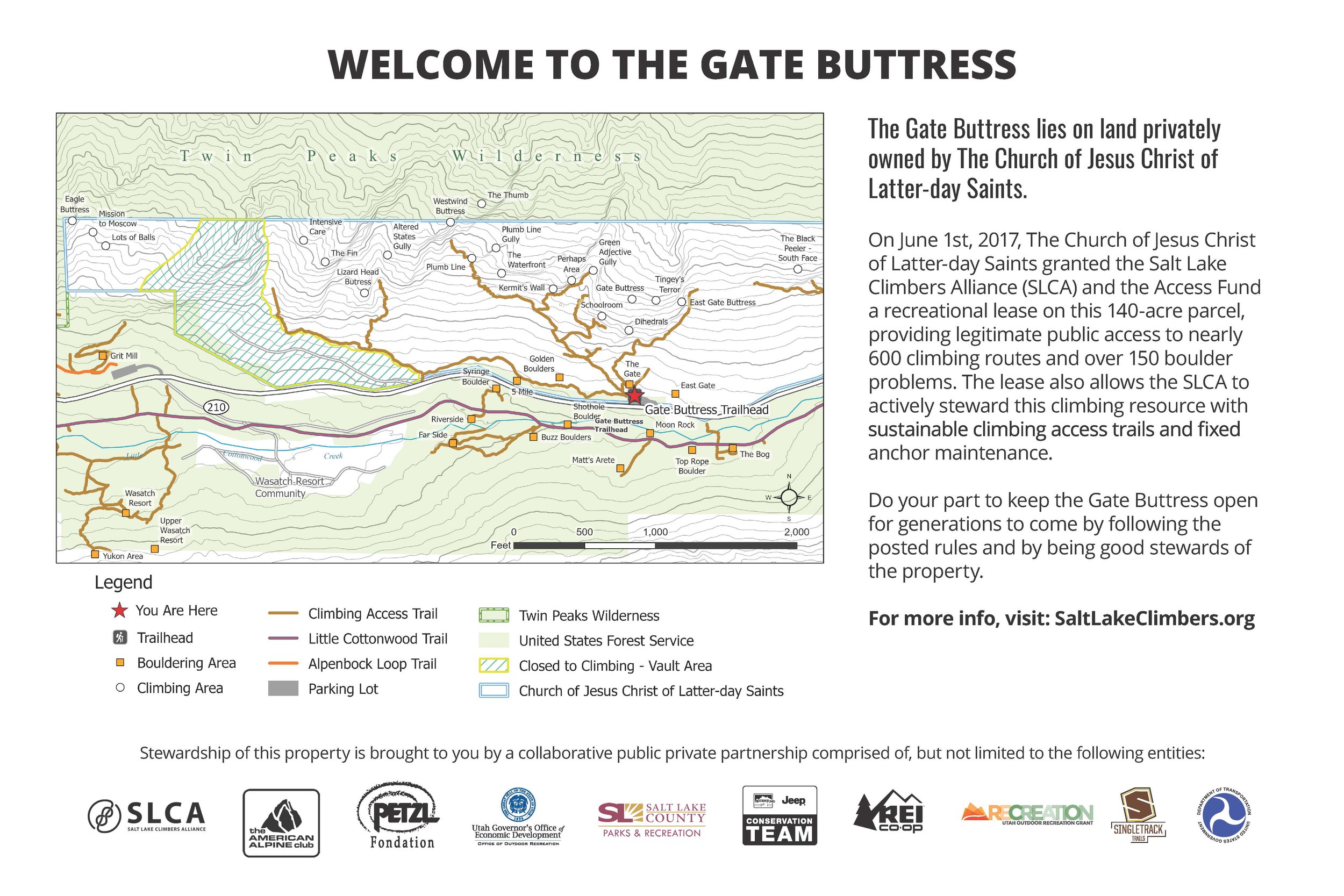

The Gate Buttress lies on private land owned by the LDS Church.

In 2017, the Church granted SLCA and the Access Fund a recreational lease to provide public access and stewardship of:

Nearly 600 climbing routes

Over 150 boulder problems on 140 acres

This lease allows SLCA to:

Build and maintain access trails

Replace and inspect fixed anchors

Promote responsible climbing behavior

*Show map of Gate Buttress

*Note: The Gate Buttress property cannot be accessed from the Alpenbock Loop or Grit Mill parking lot because of the Church vaults.

Historic Bouldering Ratings

Lower half of the historic site includes:

9 bouldering areas

Problems rated V0 to V12 using the V Scale, developed in the 1990s by John “Vermin” Sherman at Hueco Tanks, Texas.

Easiest: VB (Beginner) and V0

Hardest (currently): V16 to V17

Some variation exists between V-grades depending on local styles and conditions.

*Show Photo 10 – Club members working at the boulders

*Show Photo 11 – Shot Hole boulder and routes

Shothole: 4 routes, V1–V8

Copperhead: 13 documented routes, V0–V13

Stop 8 – Industrial History of the Canyon

*Stop with the group at the concrete remnant with the large partial hole

*Show Photo 12 – Off-width boulder with Royal Robbins

Royal Robbins was a pioneer of American rock climbing, known for many first ascents in Yosemite National Park and for being a strong advocate of clean climbing (without bolts and pitons). Starting in the late 1960s, his ethical approach helped redefine climbing culture across the U.S.

Robbins is also considered one of the originators of modern bouldering, and his presence here in Little Cottonwood Canyon links this area directly to that broader climbing legacy.

Historic Infrastructure

This trail once supported a water pipeline that ran through the canyon.

Concrete and metal remnants of the system still exist along the trail and in the surrounding vegetation.

*Show Photo 13 – The rail line up the canyon, circa 1880

Little Cottonwood Canyon has a deep industrial past:

Granite quarrying began in the 1860s

The first railroad was built in 1873 to haul ore from Alta and granite from the quarry

The line was modernized several times and operated through 1918

Beside the railroad was:

A rudimentary road for wagons (and later, cars)

Water treatment and power plants, versions of which still exist today

*Show Photo 14 – Miners at Alta

This photo of Alta miners captures another layer of the canyon’s history—the mining boom that shaped infrastructure, economy, and use patterns in the canyon. These miners helped spur the development of transport systems and resource extraction that left a lasting imprint on the landscape.

Alongside these industrial activities were early water and power facilities, some of which still operate today.

*Show Photo 15 – The Murray Power Plant

The Murray Power Plant is a reminder of the early industrial infrastructure tied to Little Cottonwood Canyon’s water and energy resources. Power and water management facilities have long played a role in shaping land use in the lower canyon, and while some still operate today, their presence contrasts with the otherwise natural landscape.

*Show Photo 16 – The Church vaults as seen in the 1960s

The Church granite mountain vaults are intrusions.

*Show Photo 17 – The grit mill

A grit mill was operating near here — at the upper trailhead — by 1953. It was used to sift and crush granite into turkey grit. These small granite particles aided digestion by lodging within a turkey’s gizzard to grind feed. The mill operated for about a decade, then remained vacant until it was demolished in 2014 by the Wasatch Legacy Project — a partnership of the Forest Service, Snowbird, and SLCA — due to its use as a vandalism site.

A second derelict structure, the Whitmore Pavilion, located across the canyon along the LCC Trail, was also demolished and the site rehabilitated for similar reasons.

Historians consider the parking lots, small subdivisions, and even the Church vaults just above here to be negative impacts to the historic and scenic character of the site and canyon — though to a far lesser degree than extractive or industrial development.

Many of you may know that a gondola has been proposed in this canyon to help alleviate winter traffic. If constructed, the gondola would:

Be up to ten stories high in some locations

Include enormous concrete tower footings

Pass directly overhead at this very site

This project would represent the most significant negative impact to the historic climbing site — permanently altering the viewshed and integrity of the landscape.

Stop 9 – Wrap-Up and Thank You

We have arrived back at our origin point.

Thank you for attending this tour of the historic Little Cottonwood Canyon Climbing Area. Please consider joining the Salt Lake Climbers Alliance (SLCA) to support our mission and more programs like this — designed to document, educate, and advocate for climbing preservation.

Join us in Big Cottonwood Canyon for future historic climbing hikes!

Final Quote – Ron Kauk

“It amazes me to realize how sacred granite is, what it has provided — from sculptured works of art to the offering of a way of life.

The opportunity to write ourselves into these boulders and granite walls has created stories that can help us understand who we are.

Learning skills to overcome obstacles that become symbols of life’s journey.”

About the Film

Stay tuned for the original short film, Alpenbock.

Climbing is part of what it means to be a Utahn — a legacy still celebrated by a new generation of climbers today. But with growing interest comes growing responsibility: we must protect and preserve these historically rich places.

“We can save a place a thousand times, but lose it only once.”

Because of community advocacy and stewardship, the experience of climbing here — from the 1960s to today — has remained largely unchanged. Though the sport evolves, the routes, the landscape, and the passion remain the same.